As it happens, a data warehouse isn’t that different. Ultimately, it’s a convenient way of storing large quantities of data. The key term here is ‘convenient’.

In one type of data warehouse, convenience is maximised for storage. It’s made as easy as possible to load data and hold it securely. This is the approach taken, in a different field, by major books repositories such as the British Library: as books arrive, they’re simply stored on the next available shelf space with no attempt to try to put them into any kind of order, whether of author or of subject matter. The label that goes on the back of the book simply indicates where in the shelving it’s stored and tells you absolutely nothing about the nature of the book or what’s in it.

|

Trinity College Dublin |

This approach is ideal for storage, hopeless for retrieval.

A great many data warehouses, and in particular most of the older ones, are of this type.

The data is securely stored and, as long as you can go straight to it and find exactly the information you want, then it’s fine to hold it that way. However, if you want to do something a little more sophisticated, say you want to start collecting related groups of information, this method is no good at all.

What you need in these circumstances is something less like the British Library and more like a bookshop. There the books are collected first by subject matter, then by author or title. The beauty of this is that as long as you know the structure, you can find not just the particular book you want but also get quickly to other, related books. You wanted a book about travel in Spain – you may well find a whole shelf of them including not just the one you were looking for but perhaps another which is even better.

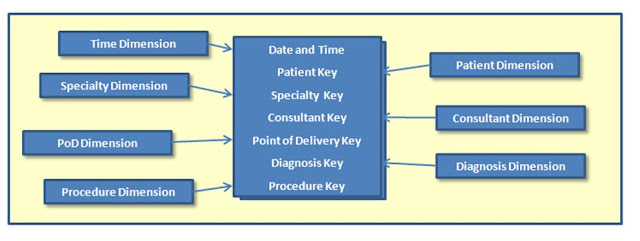

Of course, when it comes to data you can do far, far more than a bookshop. Because pulling the data together into various collections can be done simultaneously in many different ways. I’m sold on the approach known as dimensional modelling. What this means, from a user point of view, is that a healthcare data warehouse would contain lists of patients, dates, specialties, consultants, diagnoses, in short of anything that can be regarded as a ‘dimension’ or classification of your’. Each of these lists is linked to a set of facts about what was done for any patient at any time.

|

| A fact table at the centre, dimensions linked to it |

That’s a bit like knowing that John Le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy is simultaneously stored under spy novels, under fiction about the cold war, under Le Carré but also under his real name of David Cornwell, under books published in 1974, and under any other category that some user might find interesting. And, because we’re talking about computer technology, it’s under all those categories although there’s actually only one copy of the book in the bookshop.

Now that’s a warehouse structure designed to optimise retrieval rather than storage, and therefore to make reporting particularly easy. That’s why this second more modern approach to structure is so much more to be preferred than the older one.

But then there’s one other aspect of data warehouses which makes them particularly powerful, whether they’re of the older or the newer type.

They can include rules engines which manipulate the data.

If the incoming data is of poor quality, rules can tell you so: in the bookshop example, you’d get an alert saying ‘the author’s name is illegible’, ‘the date of publication isn’t given’ so that you can get the classification information improved.

If you need to add new information derived from the incoming data, rules can do that too: if you know that data from one department in the hospital shows the consultant identifier as a code, say ‘MKRS’ and you want it to be stored as ‘Mr Mark Smith’, you can define a rule that adds the form you want. In the bookshop example, it could add ‘David Cornwell’ to John le Carré’s name.

Taken together, these aspects of data warehouses – structures optimised for reporting and the application of well-defined rules – make them absolutely essential tools for understanding healthcare activity. They can take raw data and turn them into management information. With the difficult management decisions that lie ahead, that’s more crucial than ever before.